“Rumble in the Jungle: The Story of Force 136” was a tribute to the Chinese Canadians who signed up for this dangerous and secretive mission in Southeast Asia during the Second World War. Launched on Saturday, May 14, 2016 were fortunate that some members of this elite group were still alive, and nine of them managed to make it to the opening.

The reason for Force 136.

In late 1941, Japan had entered the Second World War. It quickly invaded and occupied large swathes of Southeast Asia. Many of these areas had once been British, French and Dutch colonies.

Britain was desperately looking for a way to infiltrate the region. They had had some success in occupied Europe when Special Operations Executive (i.e., British intelligence) trained and dropped secret agents into France, Belgium, Holland, etc. The role of these agents was to organize and support local resistance fighters, and help with espionage and sabotage of infrastructure and German supply lines and equipment.

Map of Japanese occupied areas of Asia during WWII

However, Southeast Asia presented some unique challenges to SOE. It was a vast area to cover, with many islands, challenging physical terrain and very diverse populations and languages.

SOE soon realized that Caucasian agents would stand out too much and would struggle to gain local trust. After all, most of the residents of the region held little good will towards their former colonizers.

The British would need an alternative agent. And an alternative strategy to build guerrilla groups.

Scattered throughout the region was a sizeable population of Chinese. Many were vehemently opposed to Japanese occupation and were angry about Japanese aggression in China. The question was how to contact and organize them?

The answer, of course, lay with Chinese Canadians. They could easily blend in to the population. They could speak Cantonese. And there were lots of these men waiting for an assignment.

In the early years of the war, many young Chinese Canadian men had walked into recruitment offices and offered their names. Generally, they were told “we can take your name, but you are not likely to be called up because you are Chinese.” They were shown the door.

Suddenly, they were the perfect recruit and their services were needed. But in a way that would require them to swear to secrecy and face a 50-50 chance of being killed.

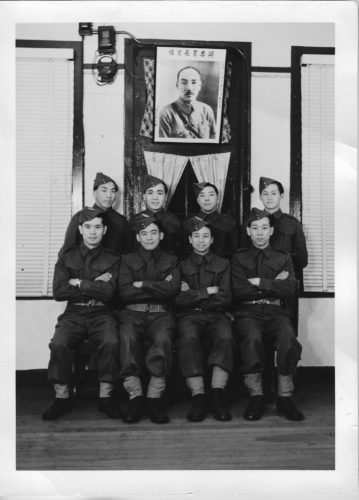

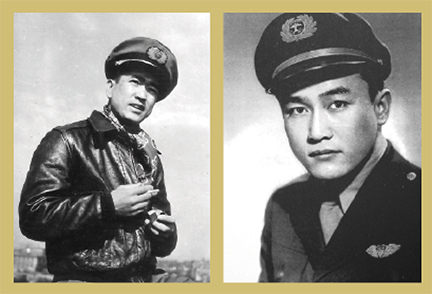

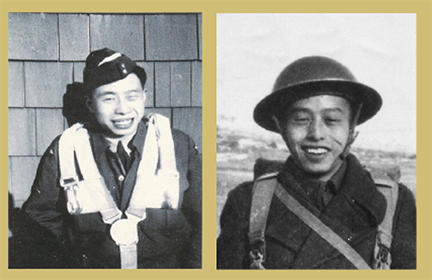

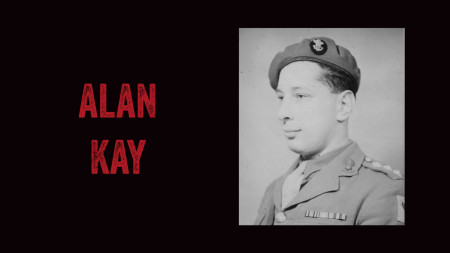

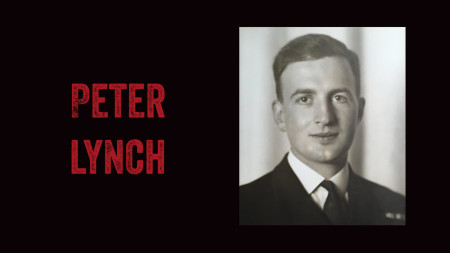

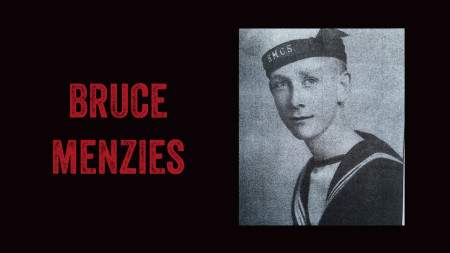

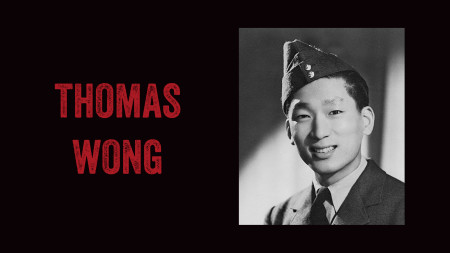

Chinese Canadian recruits

Between 1944 and 1945 about 150 Chinese Canadians were recruited and quietly seconded to the British SOE in Southeast Asia. They became known as members of Force 136.

No ordinary training:

The mission of Force 136 members was simple. Get dropped behind Japanese lines; survive in the jungle in small teams with no outside support; seek out and train local resistance fighters; and work with those guerrilla groups to sabotage Japanese equipment and supply lines and conduct espionage.

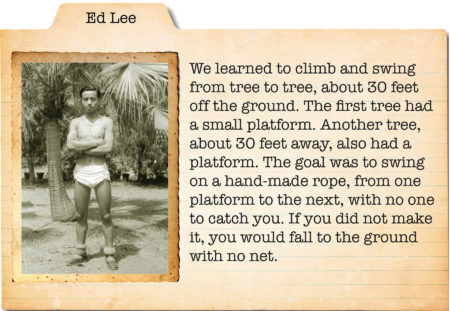

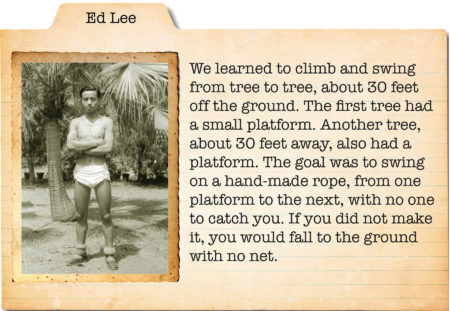

To do this kind of work would require much more than their basic army training. The men would need to learn commando warfare techniques. Over the course of several months they learned such skills as: stalking; silent killing; demolition; jungle travel and survival (including how to swing from tree to tree); wireless operations; espionage; parachuting; interpretation; and silent swimming.

Swimming was one of their biggest challenges as most Chinese were banned from public pools at the time, so few knew how to swim.

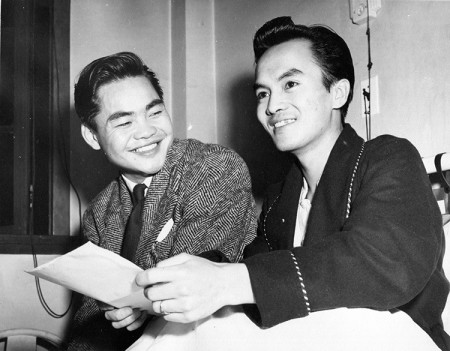

John KoBong and Tom Lock learning to swim silently loaded down with gear.

Besides their gruelling training, the men would have to fight off illnesses (like malaria, dysentery and broken bones), and endure incredible heat, humidity and monsoons.

Ed Lee recalls some of his training.

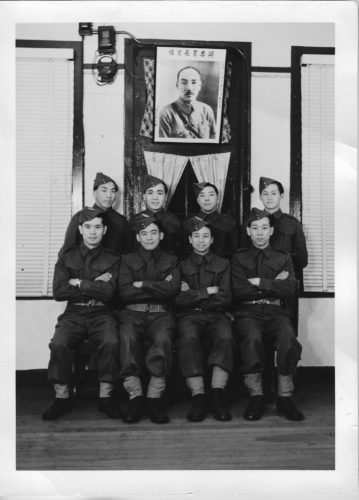

Eventually, each recruit became a specialist: in demolition, wireless operations or interpretation. In the field, teams were small and generally consisted of no more than eight men: first and second commanders, two demolition experts, a wireless operator, a coder/decoder and two Gurkha scouts.

The First Recruits:

The first group to be formed were 13 hand-picked men who were assigned to a mission with the ominous title: Operation Oblivion. Their initial goal was to go into China, but the Americans vetoed those plans.

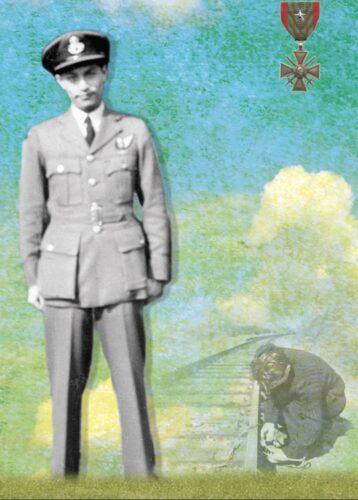

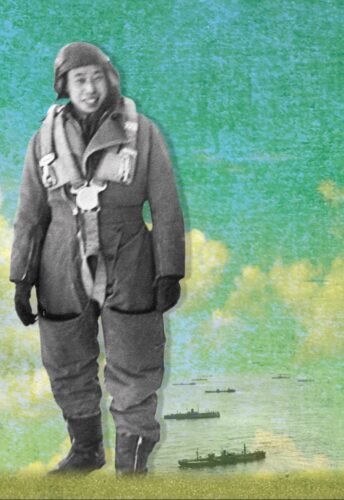

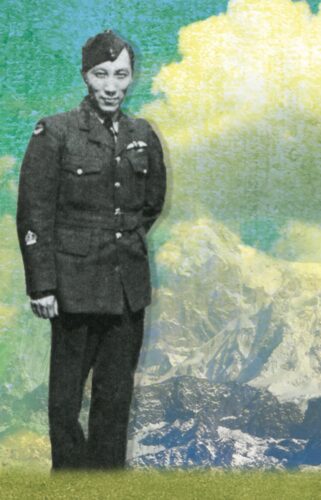

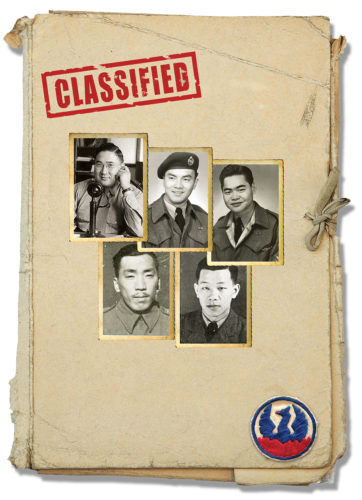

First of the Force 136 recruits, also known as the Operation Oblivion group.

They endured three-months of exhausting training at a secret, temporary camp at Commando Bay on Okanagan Lake. Training continued in Australia on Fraser Island where the men were attached to the Australian Army.

Later Recruits:

By January 1945, the remaining Chinese Canadians had been recruited. The first of these men were shipped to India via England. Others followed them to India over the next few months. About 15 men were selected to go to Australia to join the Operation Oblivion group.

Chinese Canadians of Force 136 training near Poona, India

The Operations:

Most recruits were not fully deployed before Japan officially surrendered on August 15, 1945. Some had had the chance to do short trips into occupied territory.

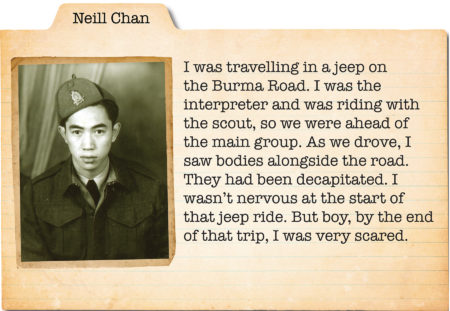

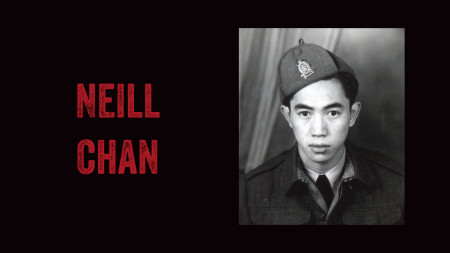

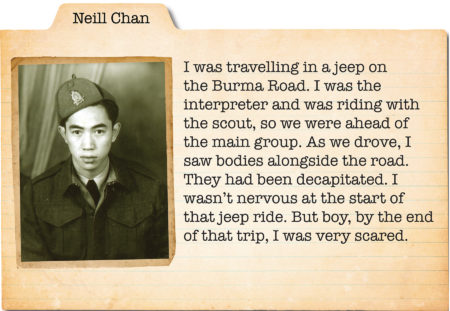

One young Force 136 member in India, Neill Chan of Vancouver, described one of these short missions which was, nevertheless, nerve wracking for him.

About 14 men found themselves operating behind Japanese lines for several months in Burma, Borneo, Malay and Singapore. Most stayed in the field well into the Autumn of 1945.

They served in missions with codenames such as Operation Galvanic, Operation Humour, Operation Tideway Green, Operation Snooper and Operation Sargeant.

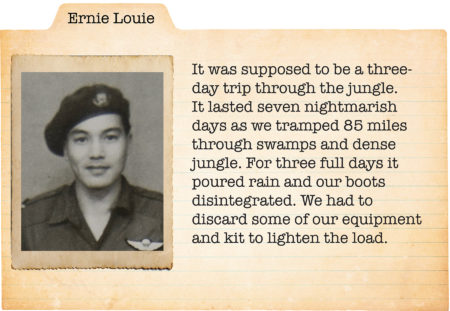

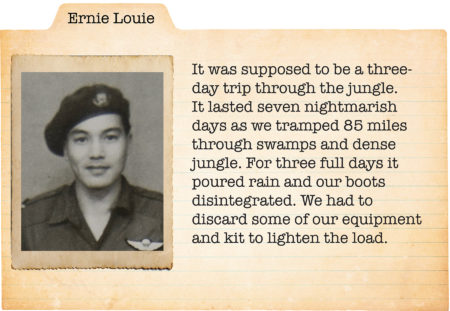

Ernie Louie recalls his days trekking through the jungle

The goals and the resistance groups they contacted varied. Generally, missions ranged from supporting and training local fighters in sabotage activities; to forcing Japanese units to surrender; finding and liberating prisoner-of-war camps; and maintaining order and security post surrender.

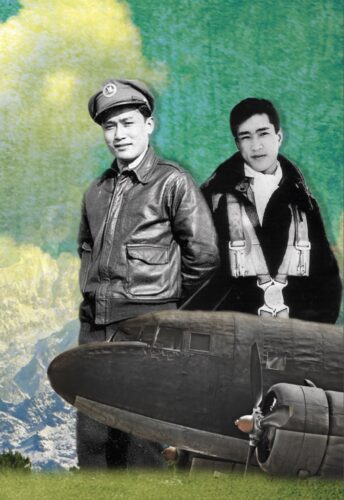

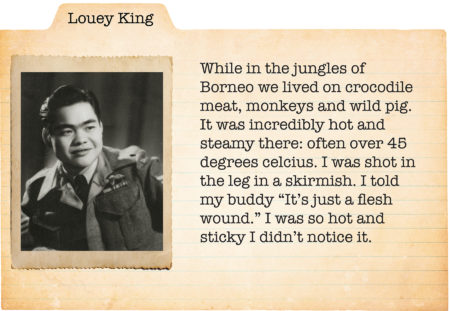

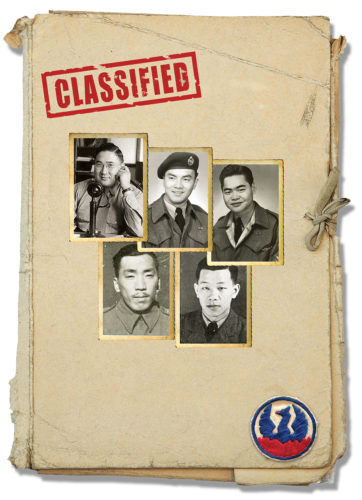

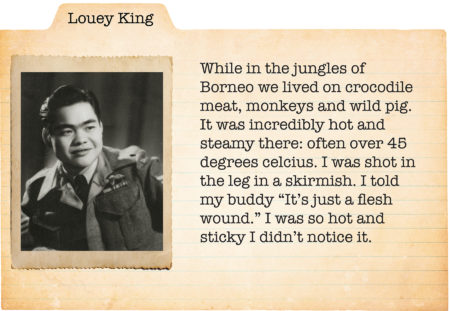

Five Force 136 men spent several months behind enemy lines in Borneo. (Clockwise from top left): Capt. Roger Cheng; Norman Low; Louey King; James Shiu and Roy Chan.

Captain Roger Cheng took in the very first group of Force 136 Chinese Canadian men. In March, 1945 he was sent into Borneo with Roy Chan, Louey King, Norman Low and James Shiu.

Their mission included: Contact and befriend Dyak headhunters; provide equipment and training; assist with sabotage; locate isolated Japanese units and force them to surrender; find POW camps; organize tribesmen into local security forces; patrol rivers; and prevent revenge massacres of Japanese troops and suspected collaborators.

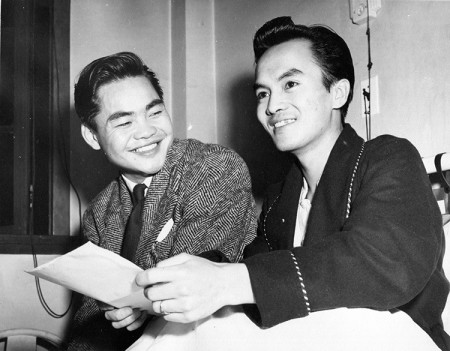

They all survived their mission in the jungle and returned home to Canada in February, 1946, as seen in this photo taken by the Vancouver Sun newspaper. Later that year, Low, King, Chan and Shiu were awarded the Military Medal for their efforts.

Awarded the military medal in September 1946: Louie King (L) and Norman Low celebrate in the hospital where Low was recovering from complications due to malaria. Because Low had previously been sworn to secrecy, he could not divulge his mission and consequently his doctors were initially skeptical that he had malaria. Low never fully regained his health and died at the age of 37.

The Long Journey Home.

On August 15, 1945 Japan officially surrendered. For many Chinese Canadians in Force 136, it meant it was time to get ready to return home.

Others stayed in the field for a few more months to find and disarm isolated Japanese troops and to help maintain order during the post-war transition period.

Force 136 member Gordon Wong returns home from the war to Vancouver. The Vancouver Sun newspaper captured his warm greeting from his sisters Violet (L) and Mabel.

Force 136 men who had been stationed in Australia, were forced to find work on cargo ships in order to earn their passage home to Canada.

Force 136 men (who were stationed in India) await in England for repatriation to Canada.

Learn more about the story Force 136 from this article published on War History Online.

Our Exhibition Launch:

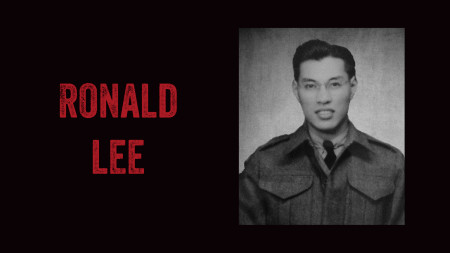

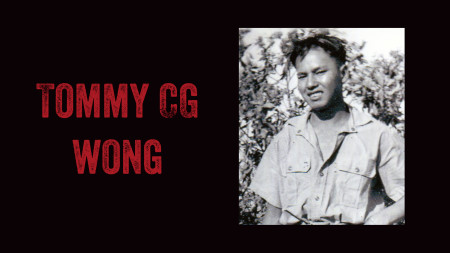

We were fortunate that some members of this elite group were still alive on May 14, 2016, the day of our launch. Nine of them managed to make it to the opening: Neill Chan, Chong Joe, Charlie Lee, Ronald Lee, Gordon Quan, Gordon Wong, Hank Wong, Tommyc CG Wong and Victor E. Wong.

Below are photos from exhibition launch event. Photos courtesy of Steve Ko and Vincent L. Chan.

-

-

Curator Catherine Clement takes the vets on a tour of the Force 136 exhibition.

-

-

Vets review index cards containing memories of their time at war

-

-

L-R: Tommy C.G. Wong, Ronald Lee & Catherine Clement, Curator CCMMS

-

-

Curator Catherine Clement explains the challenging training to Minister Harjit Sajjan

-

-

Curator Clement shows some interesting documents to Minister Sajjan, Minister Wat and Minister Anton

-

-

L-R: Curator Catherine Clement, Minister Harjit Sajjan; BC MInister of International Trade Teresa Wat; and BC Attorney General and Minister of Justice Suzanne Anton.

-

-

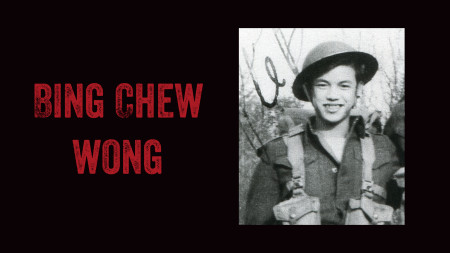

Minister of National Defence, Harjit Sajjan shakes hands with Bing Wong

-

-

BC Attorney General and Minister of Justice Suzanne Anton says hello to Chong Joe

-

-

President King Wan speaks to a standing room only crowd.

-

-

Minister of National Defence, Harjit Sajjan speaks to the veterans

-

-

Force 136 veteran Neill Chan takes a stroll through the displays

-

-

-

Chong Joe

-

-

Charlie Lee with his family

-

-

Force 136 vet Ronald Lee and Minsiter of National Defence Harjit Sajjan

-

-

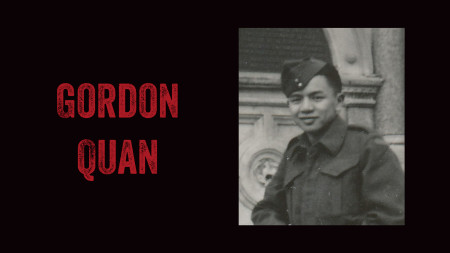

Gordon Quan, Victoria, B.C.

-

-

Gordon Wong came from California for the event

-

-

Hank Wong (centre), who came from London Ontario with his son Rick Wong, poses with curator Catherine Clement.

-

-

Veteran Tommy C.G. Wong and Trevan Wong

-

-

Victor E. Wong

-

-

L-R: Gordon Quan, Hank Wong and Hank Lowe.

-

-

Vets cut the special Force 136 cake. L-R: Hank Lowe, Gordon Quan, Tommy Wong, Charlie Lee and Ronald Lee.

Exhibition Supporter:

Exhibition Partner: